Factorization Analysis of 35, 130, and 72

This linked YouTube video (factoring 35, 130, 72) shows the analysis of three factorization diagrams: 35, 130, and 72. The numbers are listed in increasing level of difficulty. The more factors in the factorization, the more difficult it is to analyze the diagram. Thirty-five can be factored as 7 x 5; 130 can be factored as 2 x 13 x 5; and, 72 can be factored as 2 x 2 x 3 x 3 x 2. There are many ways to factor these numbers with a corresponding number of diagrams. I will go through one example for each number. In my class, we use iPads and the Doceri app to create and analyze these diagrams. The videos are created using Doceri, Keynote, and iMovie. An important aspect of this work is that the software is freely available. My students were given an iPad so with the free software, they were able to do this work.

To begin a factorization analysis of a number, look for equal groups of dots in the diagram. The number of equal groups is the first factor in the corresponding multiplication problem. Thirty-five begins with 7 equal groups; and, both 130 and 72 begin with 2 equal groups. Thirty-five has 5 dots within each of the seven

groups. Its factorization is complete. 130 has a set of thirteen nested groups within each of the two large groups. There are 5 dots within each of the smaller 13 groups. Thus, the factorization of 130 is 2 large groups of 13 smaller groups: 2 x 13 = 26 of these smaller groups. Within each of these 26 smaller groups are 5 dots: 26 x 5 = 130 total dots.

2 x 13 x 5 =

26 x 5 =

130 dots

Within the factorization of 130 is a factor of 10: 2 x 5. It would be useful for students to factor and diagram 10 x 13 as 2 x 5 x 13 or 5 x 2 x 13 and compare these diagrams to the original 2 x 13 x 5. This activity would provide experience with 10 groups of 13 (multiplying by 10), or, if the order was changed to 13 x 2 x 5 or 13 x 5 x 2, the drawing becomes 13 groups of 10. These different drawings of the same set of factors build a conceptual understanding of factors, multiplication, and place value (grouping by tens) as well as the commutative property. These simple changes result in vastly different diagrams.

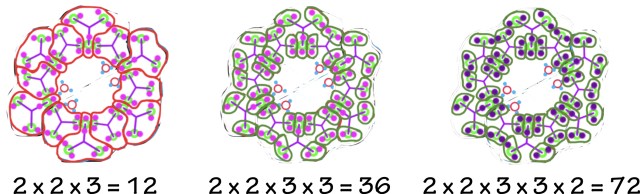

The factorization of 72 also begins with 2 equal groups. Seventy-two is the most difficult three numbers, even with factors of only twos and threes! Begin with the two large

groups and, then, loop two smaller groups within each of these larger groups: 2 x 2 = 4 groups (blue). There are 3 smaller groups within each blue group (red). There is a total of 12 red groups (2 x 2 x 3 = 12). Within each red group are three smaller groups (green) for

a total of 36 very small groups (2 x 2 x 3 x 3 = 36). Finally, there are two dots within each of these very small groups that equal the 72 total dots (2 x 2 x 3 x 3 x 2 = 72).

I will continue to analyze student diagrams, create my own diagrams, and provide both video and text explanations. These ideas take much time and effort to build understanding. The main thought is that students have a way to conceptualize theses ideas.

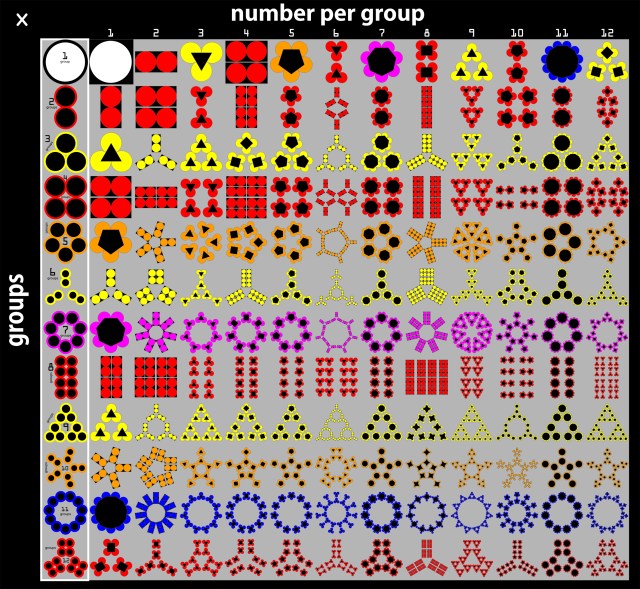

A Multiplication Table based on Factorization Diagrams

Many of my sixth-graders do not know their math facts, nor do they have a desire to learn them. To develop an engaging way for kids to practice math facts and, consequently, learn those facts, I have designed a multiplication table using prime factorization diagrams:

Note the use of the commutative property; for example, compare 3 groups of 4 (3 x 4) with 4 groups of 3 (4 x 3).

PDF; both white and gray background

To be continued with a table made of student work; a format for students to follow to create these diagrams in Doceri; proper credit to Brent Yorgey.

Change the Divisor; What is the corresponding change in the quotient? It’s the RECIPROCAL

The tables are provided for my sixth-graders to design their own fraction word problems. As the title suggests, students will then investigate what happens to the quotient when they change the divisor. This first table guides students through designing an initial set of problems. The second table provides a broader, less defined set of choices.

The Divisors and the Quotients: as one increases, the other decreases; they move together as reciprocals

One goal for my sixth-graders is for them to think about fractions most days throughout the school year. That thinking is not simply solving problems, but exploring the relationships of the numbers within the problems. An example is teaching kids why they multiply by the reciprocal to solving a “dividing by fraction” problem.

Place Value #2: base ten to place value

1. Challenge: write what you know about place value and number systems

2. Ones and Zero (ones; units)

3. The Tens Place

4. Counting to 1310 in Five Different Number Base Systems

5. Drawing the “Tens” Place (101) in Five Different Number Base Systems

6. The Language of Different Bases

ANOTHER CHALLENGE: naming numbers in different bases

7. Drawings and Names for 1112, 1113, and 11110

1. A Challenge

This post is my mental meandering about place value, base numbering systems, and their relationship. I am sorting through what and how to present place value and our base ten system of numbers to my sixth graders. There is much more here than I plan to present to them. This detail helps me sort through what to do. Before reading this post, I suggest that you write about how the position of a digit affects its value (place value) and base ten numbers. Remember that ours is a base ten place value system. Try to explain a base two system, although this system is difficult to explain. Other systems are easier to explain because the pattern becomes apparent. Explain a higher number systems such as base three or base four, then try to explain base twelve! I find this post difficult to write. This difficulty in writing reveals how confusing are the concepts of place value and base ten numbering system. It is important to have students work through many seemingly simple examples. Students must talk through the problems, explain the problems, and be able to write down those explanations.

[back to the top]

Hopefully, you have tried to write something. So, here goes …

Continue reading

Place Value #1: 10 groups to groups of ten (tens)

As a sixth-grade math teacher (or any math teacher fourth-grade and above), you have probably told students that the value of a digit is ten-times greater as you move each place value to the left. This is true: 5 ones becomes 50 ones (5 tens). I have said this to my students. But, as I write these posts and think carefully about my students’ difficulty in understanding math, I realize that this simple statement is complex. To conceptualize “ten-times greater as moving from ones to tens” is difficult. Even as I write this, I think, “C’mon Steve, this is silly; 5 ones to 5 tens is ten times more. It is not that hard!”.

Beginning Multiplication #1

Students will begin by discussing multiplication as equal groups of things. They will provide examples of “things” and “groups”. I will give kids some things to work with: centimeter cubes, pennies, beans; and, some containers in which to place those things: plastic bowls, coffee cans, circles on paper. Take the time to have kids do this. Sixth-graders need this time. Have them think about it – all aspects of it: things, groups, equal groups – write about it, and explain it. Students should include drawings in their writing – what are the images that they are building in their heads as they work through these simple examples?

How to Support the Core Math Class

This next school-year, I have an opportunity to teach math within my science and social studies classes. Our sixth-graders simply need more minutes to think about and work on mathematics. The students and teachers at my school are grouped into villages of 75 to 90 students. The students are divided into three groups who move together between their math, science, social studies, language arts, PE, and exploratory classes. This next year, I will be able to take some minutes from my science and social studies classes to teach math.